Beyond Cards and Codes: Unraveling Brazil’s Pre-Pix Payment Maze - Part 1

Before diving into the state of the Brazilian payment landscape leading to the introduction of Pix, it’s essential to understand the various components that make up a payment ecosystem. Each component plays a distinct role, often intertwined, to ensure the smooth functioning of the system. In this specific case, understanding the complex set of incentives created through card schemes, bank conventions, and other dynamics is a key element to solving the puzzle of ‘what made Pix such a tremendous success’.

A payment scheme is the “rulebook” of a particular payment method. It sets out the rules, standards, and procedures that dictate how transactions are executed, cleared, and settled. This encompasses the rights, responsibilities, and obligations of all participants.

The payment infrastructure is the “machinery” that facilitates transactions. It includes the technological and operational frameworks, like hardware, software, and communication channels, ensuring transactions are efficient, secure, and reliable.

A payment scheme institution is the “architect” behind a payment system. This entity usually designs the payment scheme and could also be involved in developing or commissioning the required infrastructure.

Payment institutions act as intermediaries in the payment process. These entities are licensed to provide payment services to end users. Their roles vary, from facilitating funds transfers to managing electronic money.

The regulator, often a central bank or a designated governmental body, oversees the entire payment landscape. It ensures the payment system’s stability, reliability, and fairness, setting standards and guidelines and ensuring compliance.

With these components in mind, let’s explore Brazil’s payment landscape before introducing Pix and see how these various elements interacted and evolved.

The Last Decade

Before the introduction of Pix, Brazil boasted an intricate patchwork of payment schemes in different flavours. Open schemes managed by government authorities like TED, open schemes managed by private companies like Visa and Mastercard and yet closed schemes managed by the banks themselves.

Card adoption surged over the five years leading up to Pix’s launch with a consistent CAGR of 17%. Though Visa and Mastercard retained their dominance, Elo – a homegrown initiative co-founded by leading banks like Caixa, Bradesco, and Banco do Brasil – rapidly gained traction using the issuing power of its shareholders. The industry was reasonably advanced, with NFC gaining traction, settlements centralised in a regulated system and the presence of mobile wallets. The Central Bank and CADE – the antitrust authority – were already fomenting a lot of competition and innovation through new regulation, attracting more investments to the market.

Brazil also had significant use of wire transfers and invoice-based payments outside of cards. There were two predominant wire transfer forms: TED (Express Wire Transfer) and DOC (Credit Transfer Document). “Boletos” were the Brazilian version of invoice payments, but they utilised a standardised barcode format readable by any bank, containing not just payee details but also payment terms like due dates, penalties, and interest.

Both TED, DOC and Boletos are in fact payment schemes, like credit and debit cards from Visa and Mastercard. They defined the rules, dynamics, economics, and structures behind each instrument.

Wire Transfers in Brazil – Why So Many Flavours?

TED – The Express Wire Transfer Payment Scheme

It was an open public scheme, which was open to new participants adhering to a set of rules and managed by a public institution – the Brazilian Central Bank. To send a TED or a DOC, the user had to fill in the same fields: Transaction Value, Bank Number, Bank Branch Number, Account Number, and CPF (Brazilian Personal Fiscal ID) or CNPJ (Brazilian Business Fiscal ID). TEDs were supposed to be cleared and settled in just a few seconds, but the protocol didn’t account for a confirmation message from the receiving bank, properly notifying the deposit of funds. This was basically done on an assumption basis after 120 minutes – the TED rule’s SLA for returning failed transactions to the original institution. Besides that, TED was a fast instrument, but it was also expensive for end users as we are going to see later on.

DOC – The Slower Wire Transfer

Meanwhile, the DOC was another scheme, for values up to R$ 5000 that was supposed to be cheaper than TEDs. The transactions were cleared by midnight and settled the next business day, which meant the money took at least one full working day to arrive at its destination. The reason for that latency is that this conversation starts to get tricky. Underneath each payment scheme were different Payment Systems, the so-called Financial Market Infrastructures – or FMI in short. Let’s dig into them.

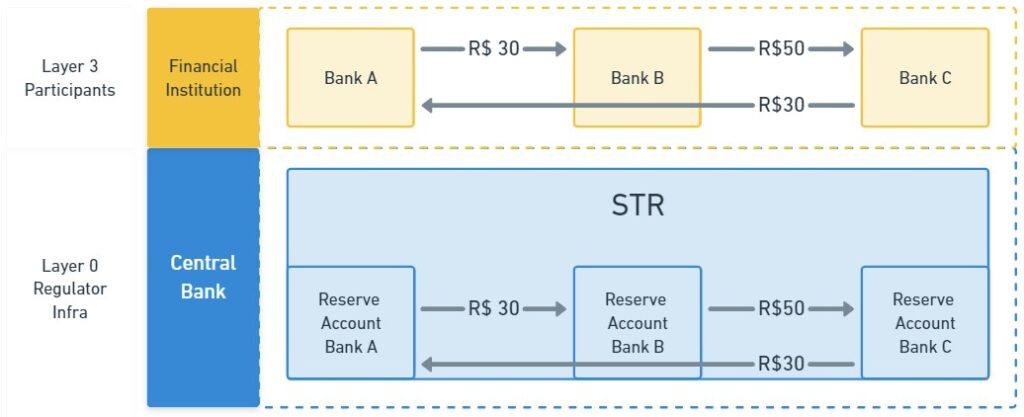

STR – The Reserves Transfering System: A 1st Layer Financial Market Infrastructure

Launched in 2002, STR served as a real-time gross settlement system, acting as the foundation of the Brazilian Payments System (SPB). All financial entities held reserve accounts at the central bank, with STR facilitating transfers between these accounts. Think of the Central Bank as the bank of the banks, their reserve accounts are basically a checking account, and the STR is the internal transfer system that moves money between two banks. Transactions on STR were fast, often settling in seconds. Pricing was based on a cost-coverage model. Despite its efficiency, STR wasn’t intended for consumer or commercial transactions. It only operated on weekdays from 6:30 am to 6:30 pm, and transfers didn’t have a message from the receiving bank confirming the deposit of funds. Additionally, the official SLA defined by the TED scheme refunds in case of failure was two hours, and reinforcement was lacking. Coupled with the rising liquidity demands, banks felt the need for an additional layer atop STR. One that would reduce their cash needs, leading to the creation of SITRAF.

Example of 3 TEDs sent using STR:

User A sending R$ 30 from bank A to user B in bank B.

User B sending R$ 50 from bank B to user C in bank C.

User C sending R$ 30 from bank C to user A in bank A.

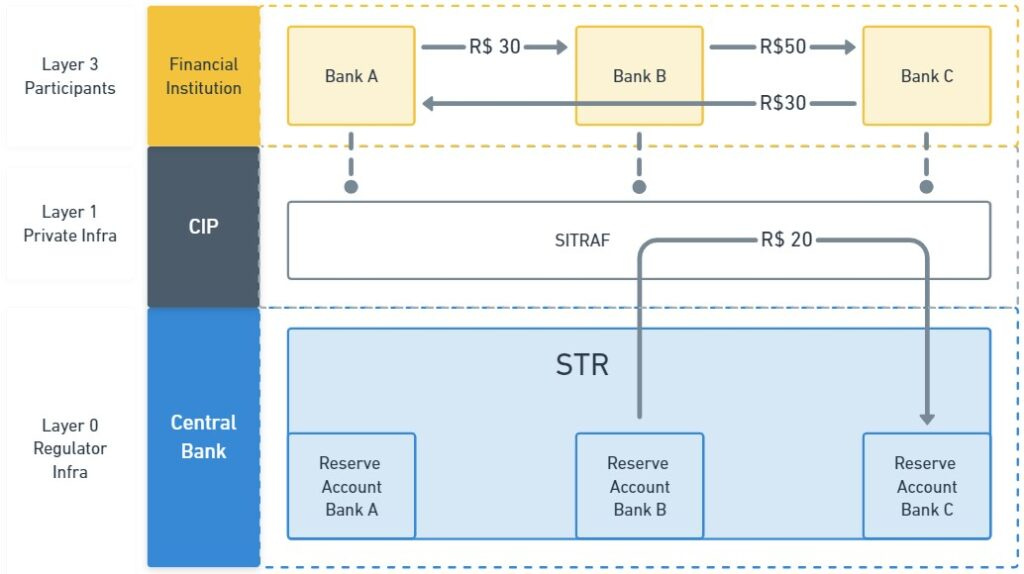

SITRAF – Funds Transfer System: A 2nd Layer Infrastructure. Redundancy For What?

While the STR was created and operated by the Central Bank, SITRAF was a product from CIP – the Interbank Payment Clearinghouse created by the Bank’s association FEBRABAN. SITRAF was a “near real-time” net differed settlement system that utilised small intervals of 5 – 10 minutes to clear transactions between banks, calculating net positions and reducing risk and the demand for cash in the system. Even though SITRAF aimed for efficiency, it came with its own cost. The banks created a private convention – a parallel set of rules – to guide TED transactions sent through SITRAF. Remember that the TED scheme already had a set of rules defined by the Central Bank and mandatory for every institution using TED.

Since transactions were usually charged from the user sending money – the Payer – a particularly contentious rule was introduced, creating the TIB (later RCO) – a fee paid by the payer’s bank to the payee’s bank – for operational costs reimbursement purposes. Reimbursing a bank for the ‘burden’ of receiving more deposits sounds almost unbelievable, but it is still true today.

In 2017 the TIB was set at an astonishing R$ 1,19 per transaction, more than 10x STR transactional fee. Even more interesting was that the private convention determined that any TED was subjected to TIB charges, regardless of the system used for settlement. Ultimately, banks might charge R$ 10 for a single TED, despite an additional and slower layer meant to ease liquidity constraints… Let’s put it together if it is unclear: they created another redundant, slower, more expensive infrastructure with an extra fee embedded as an operational cost reimbursement to limit their cash needs, and they managed to still charge everyone north of R$ 10 per wire transfer.

Example of 3 TEDs sent using SITRAF:

User A sending R$ 30 from bank A to user B in bank B.

User B sending R$ 50 from bank B to user C in bank C.

User C sending R$ 30 from bank C to user A in bank A.

Transactions are calculated in SITRAF and the resulting net position bank B needs to send R$ 20 to bank C.

Introducing Payment Institutions in STR

In the world of finance, accounts often play unique roles. Such was the case when the Central Bank created distinct accounts for banks and payment institutions. Settlement Accounts were the new addition to the system, designated for payment institutions, existing for the sole purpose of settling transactions. Imagine an account with very simple functions of sending money – both to other institutions and customers of those institutions – and receiving money from both types of senders. Meanwhile, Reserve Accounts allowed banks to conduct interbank operations and multiply currency, something that payment institutions could not do.

Besides that, Payment Institutions were also allowed to have bank accounts themselves. In fact, this was Stone’s main settlement mechanism for many years – every morning, we would send money to our account in Itau and spread the money with internal transfers to Itau’s customers.

Banks were not allowed to do that. They operated interbank operations through STR, where borrowing and lending money from each other was conducted directly in the system.

The Money Printing Machine for Stone

Stone’s venture into the STR (Brazil’s real-time gross settlement system) began with a simple need to test their newly opened Settlements account. A R$ 0,01 transaction was sent from Stone’s checking account in Itau to their STR settlement account, arriving a few seconds later. We repeated 9 more R$ 0,01 transactions and the tests were declared a success. We celebrated!

But the next morning brought a surprise. Itau had sent Stone R$11.90 for the TIB fee. After sending R$ 0,10 cents in 10 different transactions from one account – in Itau – to another – in the STR – we made R$ 11,90 minus STR operational costs of a few cents. So we repeated the tests, this time with 100 transactions. Repeating the test yielded another R$119.00.

Breaking the Convention

Stone’s team quickly realized what had happened. In their efforts to understand the system, they’d stumbled upon a loophole, inadvertently creating a money-printing machine for themselves. With deep knowledge of the rules, they knew this was a mistake and promptly sent the money back to Itau, explaining they weren’t adhering to the convention that created the TIB. The problem was, when fully operational, Stone’s STR account would make millions of transactions every month, creating an unbearable and artificially created cost.

The situation sparked confusion among the banks, leading to an endless exchange of emails, policies, guidelines, and documents. It took the intervention of the Central Bank to clarify that the TIB was not a mandatory fee. Stone had proven its point.

Emboldened by this victory, Stone began providing settlement APIs to other fintechs, rapidly becoming responsible for a significant portion of the STR transactions in a day. Realising they’d been outmanoeuvred, the traditional banks were forced to change the convention rules, reducing the TIB from R$1.19 to a few cents per transaction.

This tale of innovation, understanding, and agility paints a vivid picture of Stone’s entrance into a complex financial landscape. Through detailed study, clever innovation, and open communication with regulatory bodies, Stone challenged traditional banking norms and paved the way for a more cost-efficient and equitable system.

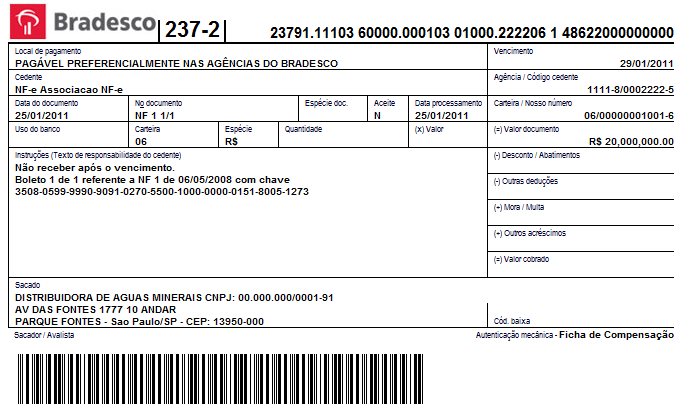

Boletos: A Unique Payment Method in Brazil

In Brazil, the “Boleto Bancário” is not merely a barcoded payment slip; it’s a financial instrument that carries a wealth of information and specific terms. A Boleto can contain a due date, clearly informing the payer of the payment deadline. If a payment is missed, the Boleto can contain calculated fines and interest, enforcing a penalty for late payment.

Additionally, Boletos can include other terms and conditions, such as discounts for early payment or specific instructions related to the purchase. These parameters are embedded within the barcode of the Boleto, allowing for automated processing by banks and payment institutions.

The adaptability of Boletos makes them suitable for various purposes, such as paying bills, purchasing goods, or even making loan payments. The ability to embed complex terms within a simple payment slip has turned Boletos into a versatile and widely accepted form of payment nationwide. Whether paid online, through a mobile app, or at a physical location, the Boleto system ensures a consistent and comprehensive payment experience, reflecting the multifaceted nature of financial transactions in modern Brazil.

SILOC

SILOC, which stands for “Sistema de Liquidação Diferida das Transferências Interbancárias de Ordens de Crédito,” is a net deferred settlement system used in Brazil.

In this system, financial transactions are not settled individually as they happen. Instead, they are accumulated over a specific period, typically a business day, and then settled all at once at the end of that period.

Here’s how it works:

Accumulating Transactions: Throughout the day, banks and other financial institutions record the transactions made between them. This includes all kinds of payments and transfers, such as interbank operations.

Netting Process: At the end of the specified period, all the transactions are netted out. This means that the payments and receipts between each pair of institutions are summed up to a single net value. For instance, if Bank A owes Bank B $100 and Bank B owes Bank A $60, the net value would be a $40 payment from Bank A to Bank B.

Settlement: Once the net values are calculated, the transactions are settled in a central location, typically the Central Bank. This might involve transferring money between the reserve accounts of the institutions involved. The deferred nature of the settlement allows for efficiency, reducing the number of actual transactions that need to be processed.

Reconciliation and Reporting: After settlement, reports are sent to the participating institutions, allowing them to reconcile their accounts and ensure everything is processed correctly.

The SILOC system provides efficiency and reduces costs for the financial system. Handling transactions in a net deferred manner minimises the immediate liquidity demands on banks and allows them to manage their funds more effectively. At the same time, the consolidated and well-regulated nature of the system ensures its reliability and robustness, contributing to the stability of Brazil’s financial infrastructure.

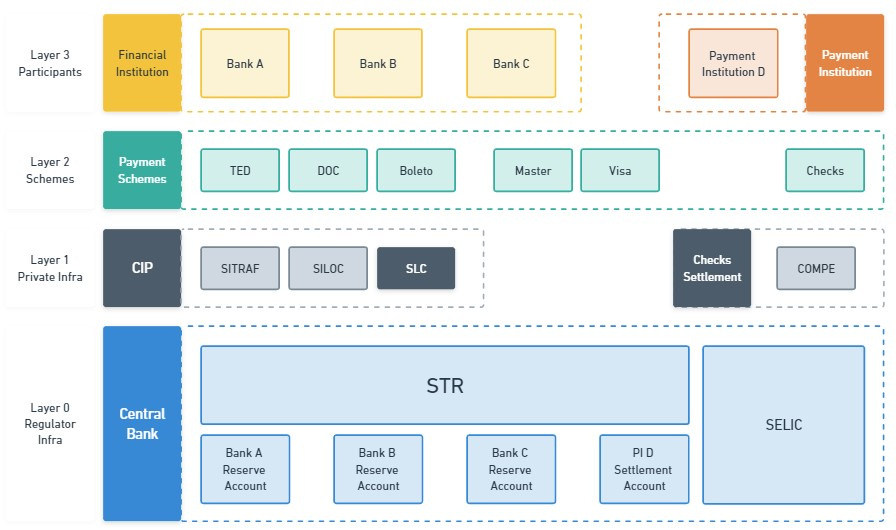

BPS – Brazilian Payment System Overview

After diving into the different pieces of this puzzle, it’s nice to look at the whole picture together. This scheme shows Brazil’s payments market layers through the last decade.

Layer 0 – STR – where the money actually exchanges hands from institution to institution. Each participant institution has to open an account with the Central Bank. Payment institutions have settlement accounts, while banks have reserve accounts. SELIC serves as a central hub where federal government bonds are held, and transactions related to those bonds are settled.

Layer 1 – Other financial market infrastructure – SITRAF, SILOC, Visa and Master legacy clearing houses and COMPE for checks.

Layer 2 – The payment schemes – with their guidelines, networks, authorisation systems and institutions.

Layer 3 – Market participants – mainly banks and payment institutions.

A second snapshot shows the addition of SLC – Sistema de Liquidacao de Cartoes – another piece of infrastructure created by CIP and made mandatory by the Central Bank for the settlement of card transactions. SLC was just a clearing layer to calculate the net position of all participants in the card schemes, using SILOC underneath to finalise the settlement process. The system went live in 2017, replacing legacy clearing houses from Visanet and Redecard.